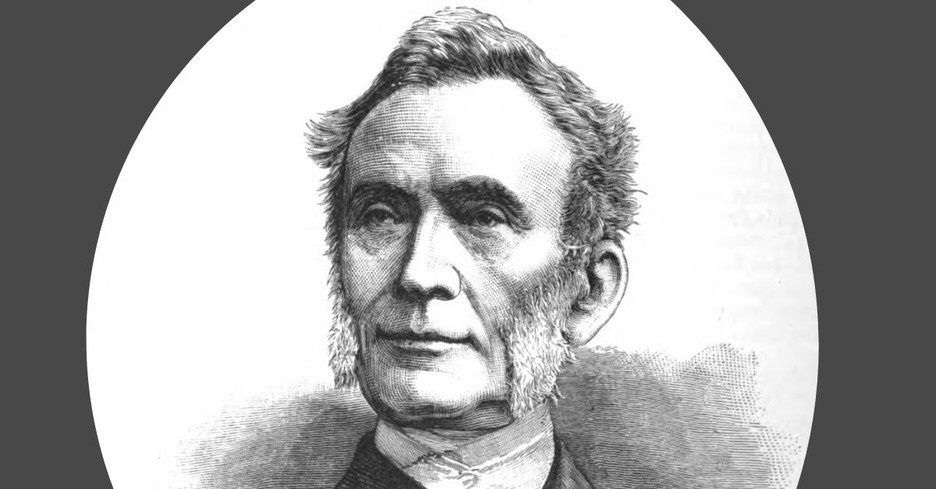

Georg, as he liked to be called (the 'e' was added when he came to England), was born in 1803 in Germany. His father, Johann Müller, developed a private plan early in life to ensure Georg's freedom from the uncertainties of war and politics. He would enter him for service in the Lutheran Church. As Georg recalled, "Not so as I might serve God‚--but that I might have a comfortable living!" And no doubt provide a comfortable and secure retirement for his father, too, in a minister's expansive country house. At age thirteen, Georg was not averse to this. A comfortable living sounded fine to him. He knew that Lutheran ministers did not actually have to live in a godly manner; they only needed to appear godly.

His father introduced Georg and his brother to money quite early on in life, giving them quite a sum "to save." He believed this would help them realize and understand the value of money. "In order," commented Georg later, "to educate us in worldly principles." But in doing this, Johann had opened up a veritable Pandora's box of worldly principles to his sons. George soon discovered that he liked spending money much more than he enjoyed saving it.

As Georg grew older, he became adept at stealing money and spending it on more adult pleasures. He recalls heavy drinking sessions with school colleagues, playing cards and reading racy novels instead of studying. He hints at darker experiences, too‚--what he later called "immorality" and "gross immorality," Victorian euphemisms for sex. He had several girl friends of questionable character who featured in his early diaries. Furthermore, he spent time in prison while studying divinity.

After beginning his studies at Martin Luther University, Müller discovered that only "decent" divinity students got decent Lutheran parishes. To be fair, he was having pangs of conscience, but the pivotal moment of Georg's life crept up on him unawares. His drinking crony Christoph Beta, newly returned to the University, boldly asked Georg if he would like to try something different from the usual run of taverns and worse. How about a prayer meeting? Something intrigued Georg about the invitation. He asked what went on, and upon being told it was Bible reading, singing and prayers, something moved him to accept. In fact, he found he was eager to do so.

God Gets Müller

Next Saturday, a dark November's eve in 1825, the two young men slipped down through the narrow lanterned and cobbled streets to the meeting. The meeting opened with a hymn, and then Friedrich Kayser knelt down and informally asked a blessing on the group. Georg was stunned. He had never seen anyone on his knees before. He himself had never prayed on his knees. He recalls it "made a deep impression on me." Suddenly, he realized he was truly happy for the first time, and a sense of peace entered his soul. But "if I had been asked why--I could not clearly have explained it." He walked back to the campus on a cloud of pure joy.

It was a turning point. Georg felt a new sense of calling in his life. He was not perfect, but he gave up his former ways, with only a few missteps. No longer was he concerned with having a comfortable country pastorate. Now he wanted to do mission work, and felt he immediately received the "peace of God that surpasses all understanding."

At first, his father was distressed by his decision, and mandatory military service seemed to derail his plans. Then illnesses made him unfit for the service and his father came around. George (the 'e' was now added) then set out for England to train with the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst Jews. He arrived in England amid much social unrest. The industrial machine had made men, women and children virtual slaves, and George felt compelled to try to help them. He had spent much time in study, but now he wanted to be active in changing the social climate. The Society was not willing to alter his training, so George set out on his own.

Paying For Your Seat in Church

At the time, most of a minister's income came from "pew rents." Those who came to church and sat in the pews were expected to pay for the privilege. The better the seat, the more a person had to pay to sit there. On top of this, ministers were allowed to accept donations, preaching expenses and seasonal gifts.

But George began to feel strongly that "the Gospel was not to be charged for." As a missionary, someone who reached out into the community, was it fair to ask those who may be searching for the truth to pay to do so? Hardly. But if there were no pew rent, who would provide for the pastor and his wife? The answer to this question, George decided, was to "just pray, and God will provide." This method forced him to be a good steward with funds and transparent about spending habits.

"Have I Gone Too Far?"

The "just pray, and God will provide" principle was not implemented without spiritual struggle. In the second week in January 1831, after continued prayers had seemingly produced nothing, Müller candidly confesses to feeling "tempted to distrust" God. "I began to say to myself I had gone too far in living in this way." It was a bad moment for him. He wrestled with this (he felt as with the devil) before feeling confident again. In fact, he records, "Satan was immediately confounded," for when he got back to his room minutes later, an Exeter lady had left them two pounds and four shillings.

In 1832, after a few years of service as a pastor in Teignmouth, he moved on to a church in Bristol. There he used the same methods of fund raising to form the Scriptural Knowledge Institution for Home and Abroad. It meant that money could be directly put into providing Bibles and portions of Bibles for local day schools and adult schools. There seemed to be a cycle of funds running to the very last straw, followed by intensive prayer and then God meeting the need.

The key method to Müller's faith walk was his certain belief that God would answer his prayers. Once, while crossing the Atlantic by boat, a delaying fog developed. George made his way to the bridge and asked the captain if there was any chance of getting into port on time. When told there was very little, he pulled the captain aside and began to pray for the fog to clear. The captain was about to follow his example when Müller apparently put his hand up. "Do not pray," he instructed. "First, you don't believe He will answer; and second, I believe he already has!" Captain Dutton walked to the door to find the fog had dispersed. We have no record of Müller ever mentioning this episode, but Captain Dutton told and retold the story many times.

The Orphans of Bristol

George had felt a burden for the abandoned children of the city streets ever since coming to Bristol. There was no educational system, no chance or hope of betterment, and no health care. To test his feelings about opening an orphan house, he began praying for God to take the thought away, but instead it intensified. He held a public meeting to propose his idea, and soon after, volunteers and gifts began rolling in.

On April 11, 1836, George opened his first orphan house for 26 female children. The success led George to open another orphan house for infant children in November, 1836. Then, in the 1840s, his desires grew more ambitious‚ an orphanage that could house 300 children. It was an unthinkable idea, because it would require a staggering sum of money. He wrote up a list of pros and cons and then waited on God. By the end of the year, gifts began arriving amid an economic depression in England. By June of 1849, children and staff moved into the orphan house. By the 1870s he had built five houses for 2000 children.

The week before his death, in early March 1898, the 93-year-old Müller, as usual, faced massive financial needs to meet the budgets on churches, five new orphanages (2,000 children and 600 staff) plus thousands of pounds committed to Bible products and missionaries home and abroad. Showing his trust in the sufficiency of God to the very end, he wrote in his diary, "The income today, by the first two deliveries was seven pounds fifteen shillings and eleven pence. Day by day our great trial of faith and patience continues, and thus it has been more or less now, for twenty-one months, yet, by Thy Grace, we are sustained."

"I Can't Take Your Money!"

Some giving George Müller could not reconcile with his conscience. If he thought a gift was made on an ill-considered impulse, could not be spared, or worse, was money that was owed elsewhere, he would challenge it. He would do this no matter how urgent the immediate need. The hundred pounds given by a poor seamstress for the first orphanage was one such gift. Only after talking to her at length was George satisfied that he could accept her money. A more difficult case was a gift from a lady of one hundred pounds at a time of very harsh need in the orphanages. George knew she had run up debts all over Bristol. He went to her and in a difficult conversation persuaded her she must take her gift back and use it to clear her debts. It was not the only time he had to do this, but it was one of the hardest, as the orphan funds that day were completely exhausted. Müller always saw such things as a test of his faith and his biblical morality. But it took some doing. Money for the orphans came from elsewhere the next day.

Operating a Godly Business

Speaking directly to Christian businessmen and women, Müller commented that although the due process of trade was fine, a Christian should specifically run his or her business in a distinctively godly way. If this was done faithfully and prayerfully, then he or she could expect God's blessing on the trade. Naturally, the keeping of good, honest accounts was one important area, as was paying debts promptly and offering good service and sound, not shoddy, goods. But Müller was also aware of other, more subtle, areas. He cautioned shop owners not to put someone outside in the street to grab customers, or dress a shop with over-rich furnishings, though all should be clean and neat (including the staff, who should be properly washed and modestly dressed!). He also believed it was wrong to sell more to a customer than he or she wanted. If a woman walked in looking for a hat, then she should leave with one, not two! Staff were to be treated kindly, paid fairly, and not expected to work overly long hours. Müller understood the importance of making income balance expenditure but maintained that good business was not driven by receipts but by honesty, integrity and courtesy in all its dealings, whether with customers, wholesalers, salesmen, workers or bankers. "Then," he said, "you will have a Christian witness, and God will honour your business."

This issue excerpted from Robber of the Cruel Streets: The Prayerful Life of George Müller of Bristol by Clive Langmead (Published by CWR, ISBN: 1-85345-395-1). Also look for the release of the new Gateway Films/Vision Video documentary based on this book.

("George Müller: God Alone Our Patron" published on Christianity.com on April 28, 2010)