What Is Calvinism?

Calvinism is a denomination of Protestantism that adheres to the theological traditions and teachings of John Calvin and other preachers of the Reformation era. Calvinists broke from the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century, having different beliefs of predestination and election of salvation, among others.

Watch Collin Hansen further describe the history and theology of Calvinism.

Read the transcript of this video by Collin Hansen:

Calvinism is described by many people in many different ways but at its essence, it is an understanding of scripture. It starts with an understanding of scripture that believes that this truly testifies to God. God himself, as he has revealed himself to us very graciously.

Also, an understanding that God is at work in this world. He is sovereignly working all things to his glory, through the renown of his name. That is the essence of Calvinism and the beauty of Calvinism is how it helps you to understand what God has done in Jesus Christ to send his one and only son to die for us, to die for people who have rejected God, who have rebelled against him, who have sinned against him. He has intervened and he is now calling to himself a people, a people who believe in the name of Lord Jesus Christ and will be forgiven of their sins and they will be with him forever more.

I think it's really ... It helps you to understand scripture, the God who is always intervening, whether it be from his creation in the beginning of Genesis to his return that we read about in Revelation. God is always actively involved with his creation, redeeming it and preparing it for his return.

How Did Calvinism Start?

Calvinism began with the Protestant Reformation in Switzerland where Huldrych Zwingli originally taught what became the first version of the Reformed doctrine in Zürich in 1519. John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion was one of the most influential theologies of the Reformation era.

Calvin's writings impressed Guillaume Farel, the Reformer of Geneva, Switzerland so much that Farel pressed Calvin to come and help the Genevan reform. Geneva was to be Calvin's home until he died in 1564 Calvin did not live to see the foundation of his work grow into an international movement; but his death allowed his ideas to break out of their city of origin, to succeed far beyond their borders, and to establish their own distinct character.

What Did John Calvin Believe?

Calvin believed that salvation is only possible through the grace of God. Even before creation, God chose some people to be saved. This is the bone most people choke on: predestination. Curiously, it isn't particularly a Calvinist idea. Augustine taught it centuries earlier, and Luther believed it, as did most of the other Reformers. Yet Calvin stated it so forcefully that the teaching is forever identified with him. Calvin said it was clearly taught in the Bible.

For Calvin, God was -- above all else -- sovereign. Like all the Reformers, he hated the way Catholicism had degenerated into a religion of salvation-by-works. So Calvin's constantly repeated theme was this: You cannot manipulate God, nor put Him in your debt. If you are saved, it is His doing, not your own.

He believed God alone knows who is elect (saved) and who isn't. But, Calvin said, a moral life shows that a person is (probably) one of the elect. Calvin himself was intensely moral and energetic, and he impressed on others the need to work out their salvation - not to be saved but to show they are saved. This emphasis on doing, on acting to transform a sinful world, became one of the chief characteristics of Calvinism.

In emphasizing God's sovereignty, Calvin's Institutes lead the reader to believe that no person -- king, bishop, or anyone else--can demand our ultimate loyalty. Calvin never taught explicitly that men have a "right" to revolution, but it is implied. In this sense, his works are amazingly "modern."

What Are the Five Points of Calvinism? (TULIP)

- Total Depravity - asserts that as a consequence of the fall of man into sin, every person is enslaved to sin. People are not by nature inclined to love God, but rather to serve their own interests and to reject the rule of God.

- Unconditional Election - asserts that God has chosen from eternity those whom he will bring to himself not based on foreseen virtue, merit, or faith in those people; rather, his choice is unconditionally grounded in his mercy alone. God has chosen from eternity to extend mercy to those he has chosen and to withhold mercy from those not chosen.

- Limited Atonement - asserts that Jesus's substitutionary atonement was definite and certain in its purpose and in what it accomplished. This implies that only the sins of the elect were atoned for by Jesus's death.

- Irresistible Grace - asserts that the saving grace of God is effectually applied to those whom he has determined to save (that is, the elect) and overcomes their resistance to obeying the call of the gospel, bringing them to saving faith. This means that when God sovereignly purposes to save someone, that individual certainly will be saved.

- Perseverance of the Saints - asserts that since God is sovereign and his will cannot be frustrated by humans or anything else, those whom God has called into communion with himself will continue in faith until the end.

The video below further discusses the Calvinist idea of "Total Depravity"

Are Puritans Actually Calvinists?

While most Puritans aligned with Reformed theology, not all Puritans were strict Calvinists. The title “Calvinist” today carries loads of theological baggage and its not always an accurate description of 16th and 17th-century Puritan ministers. Many views on numerous points of theology existed amongst the Puritans.

The Puritan minister Richard Baxter heavily debated points of theology which were affirmed at the Westminster Assembly. He engaged in heated debates with fellow Puritan minister John Owen and wrote of his disagreements with other Puritan ministers such as Thomas Goodwin and Thomas Manton. John Goodwin, another prominent Puritan minister, came to affirm an Arminian understanding of predestination.

The Fruits of Election; the Right to Revolution

God alone knows who is elect (saved) and who isn't. But, Calvin said, a moral life shows that a person is (probably) one of the elect. Calvin himself was intensely moral and energetic, and he impressed on others the need to work out their salvation - not to be saved but to show they are saved. This emphasis on doing, on acting to transform a sinful world, became one of the chief characteristics of Calvinism.

In emphasizing God's sovereignty, Calvin's Institutes lead the reader to believe that no person--king, bishop, or anyone else--can demand our ultimate loyalty. Calvin never taught explicitly that men have a "right" to revolution, but it is implied. In this sense, his works are amazingly "modern."

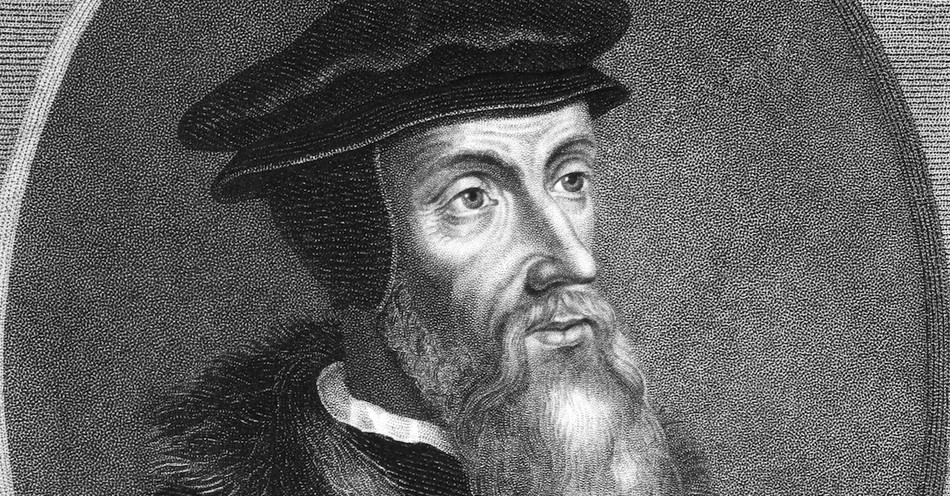

Photo Credit: ©GettyImages/GeorgiosArt

This article is part of our Denomination Series listing historical facts and theological information about different factions within and from the Christian religion. We provide these articles to help you understand the distinctions between denominations including origin, leadership, doctrine, and beliefs. Explore the various characteristics of different denominations from our list below!

Jehovah's Witnesses & Their Beliefs

Baptist Church: History & Beliefs

Presbyterians: History & Beliefs

The Pentecostal Church: History & Beliefs

Lutheran History & Beliefs